Silent Passenger

Three Shadows Photography Art Centre ,Beijing

Tim Yip Solo Exhibition

2013

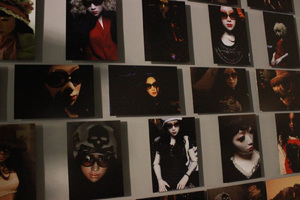

Artists’ studios are always revealing. The flow of their creativity is exposed by the order or organisation of the space. Some artists are clinical in preparation for precise movements and decisions. Others inhabit an accumulation of sources and objects as rich and interwoven as the subconscious itself. Tim Yip’s Beijing studio is an area large enough to enable design for major theatrical productions. At the time of my last visit hundreds of costume designs were pinned to a wall and there was a sense of urgency and looming deadline. The scale of his enterprise is seemingly limitless and constantly varied. He could be researching Tang dynasty interiors or men’s hats in twenties Shanghai. The creative laboratory is also a comfort zone where the artist is embedded in those elements that drive the productive forces. It is here that you see the maquettes of the past projects and even the plans for unexecuted ideas. As would be expected, Tim’s inner space is organised to offer the best viewing facilities with a large screen and comfortable seating, but around him are sculptural forms. There is evidence of a restless shaping with his hands. He is as surrounded by objects as he is by graphic imagery and photographs. The first sense you have as you enter the room – the inner sanctum – is that it is crowded. There are several seated figures. On a second glance you realise that none of them are moving and they are all young women. His serene company is entirely composed of varying incarnations of his unspeaking companion, Lili, the silent passenger.

Tim began by working as a photographer. Taking photographs for him is as natural as walking or talking. It is part of the rhythm of his daily life. The consequence is the constant framing of the surrounding world through the rectangle of his viewfinder. There is a pronounced distinction between the world experienced photographically in rectilinear balance with controlled tonal and colour values and the world of unframed vision, but it is now a universal fact that we live in such a photographically dominated environment it has become difficult to separate ourselves from the seemingly photographic composition of our surroundings. We frequently witness the world conforming to photographic or cinematic precedents. The scene along this street or across that landscape looks just like a movie. Our memories are shaped by inescapable photographic signals. My memory of childhood is like a photograph from a family album. In nineteenth-century Europe literate classes may have thought that the events of their lives coincided with a literary narrative as if they inhabited a great novel. We, today, occupy a long, film-like, visual narrative and the more intense the struggles of the daily round, such as crossing the city in the rush hour or riding on the crowded subway, the more we retreat into the idea of narrative and step back to view the passing world with some inner detachment. The world beyond our eyes becomes no more than a film or a frozen, still photograph. This switching to an alternative consciousness is a basic survival strategy for negotiating the day.

What is depressingly significant for somebody like myself, whose frequent work is to consume photographs, is that now photographs too often look like other photographs. Rarely do they break through and take us to somewhere we have never been before. Our memory banks are too full and overcrowded with lifetimes of imagery.

If Tim is not carrying a camera or using his phone to make a picture, then an assistant is photographing. At the end of the day the pictures are filed and stored, just as the conversations are recorded. There is a literal parallel between this archiving of the day’s progress, with its various points of excitement, and mental processes. The studio, just like the formal house or home, is an equivalent to the brain itself. In one part of the space the memories are archived. In another, the deeper forces in the lower strata of the subconscious come into play. Lili, in her various incarnations, lives there in the lower strata – somewhere in the centre of the studio, on Tim’s couch, where he engages with the strongest memories.

Lili looks like any number of young women one might see on the streets of a major Chinese city. She is dressed with a certain style, but reveals no trace of wealth or special quality. She is emphatically ordinary. She has not, as yet, acquired true star status, but that may be simply a matter of time. She may have ambitions. Tim has chosen her clothes, her hair and her attachments – the sunglasses and the necklaces – to convey the utmost ordinariness. If she is erotic, it is not because of any disclosure on her part like a hint beyond the usual of breast or thigh or what she is wearing closest to her skin, but because she is simply a feminine presence. Her ordinariness ensures her emptiness. She is whatever you want her to be. She is the mirror of your projections – a most agreeable companion.

She began as a life-size, hairless, standing, naked form with a definitive sex. She looked like a beautifully finished prototype for a new, to be mass-produced, manikin. She could be the body for every store in China and then dressed according to season and location. There was one distinction in this early version. She wept, silently. Tears flowed down her cheeks. A later model, finely shaped in white marble, was a lying version, with her thighs moving forward toward a foetal position and her sex exposed. I think of this Lili as being deep in dream. She already presents a kind of double presence. Her exterior is smooth marble, but her shape suggests she is in a different territory. She has been dispatched to the domain of sleep and the unconscious.

Tim needed a Lili he could transport. He wanted to dress her and photograph her. He put her on a plane and brought her to Taipei. She took up residence in an apartment. He found her at the wheel of a car, eating at a table in the market, in a crowded bar. She appeared completely confident and self possessed. Her eyes, hidden by glasses, were impossible to read. She was veiled day and night. She received full video treatment and then, in a further twist, Tim cast a young actress who donned a wig in a hotel room and played Lili for the video camera. Lili was positioned exactly at the point between the animate and inanimate. She existed on camera and then provided a role to be improvised for the camera. She was an idea, a character, a part, a visual echo of somebody once seen and the subject of a magazine story. She could easily become the subject of an adverting campaign. Some of the pictures of her could have been shot by paparazzi. She could start to appear at film premieres in some final comment about the artifice of celebrity, but that would be to reduce her. She offers more subtle provocation.

Tim admits that Lili arrived without any conscious planning. She was not a developed person, just a presence who evolved and became more defined over time. He claims that he always worked from the starting point of a female image. The view of the single woman was invariably the root element from which even his film work developed. She became a presence that was peculiar to his world, and marked not a contrived friendship, but, on the contrary, a further sign of the inherent loneliness of his working life in Beijing. She was what set him apart. Directors with whom he worked had different concerns to his. To make his work he knows he has to give up a part of himself, especially in the service of the collective act of filmmaking. Lili was to some extent the product of a need to reclaim what was his. She belonged resolutely in his world.

Since childhood Tim was conscious that there was a zone of the imagination that he could not necessarily share. We assume everybody has some sense of their interior selves, but our assumption may be false. We also suppose that all children have their imaginary territories. They must do, but adulthood in its various and brutal guises tends to crush those excursions beyond the immediate, tangible, sensually satisfiable present. The child’s creative world becomes a secret world if it is to be sustained. It exists beyond the ordinary world proscribed by the wish of ones parents or beyond their desire for their offspring to triumph in the competition of the professional or corporate ladders. Lili is like a companion in a solitary childhood, and all children have a sense of solitude as well as tribal belonging. She comes from the secret world.

For many years it was believed that photographs produced evidence of a real world. Their subject was always a tangible reality, simply because it had been observed. Photographs were offered as a kind of truth. Now we see them all as a fiction. They offer the most selective history. Unless photographs have been recorded by robots or close-circuit-camera observation, they are the result of conscious choice. Photographs allow us to frame reality. It was not until the early twentieth century that Alfred Stieglitz, in many ways a father to American modernism, described certain photographs as ‘Equivalents’. The pictures in question, in his case usually photographs of the night sky, were more important as equivalent reflections of our interior responses, as if to great music, than as descriptions of the world or of the literal shapes of nocturnal clouds. Photographs were less the agents for description and more a means to suggestion, which then took them into the realm of art. Tim, independently, began to realise that his photographs recorded more than the surface of the world. They were routes to his interior.

It is a short step from the construction of the interior world to Tim’s acquired observation that the entire manufactured world, as opposed to the natural world, was a reflection of human need and human proportion. The industrial revolution had enabled us to produce machinery to sustain us proportionally. We travelled in cars and on trains that were sized to carry us and rode elevators up buildings that were constructed to accommodate us. We industrialised production to maintain us and in turn to service our manufacturing process. The constructed world is a reflection of ourselves, from the doorway we enter to the seat on which we sit. So too is the interior world. It is another form of reflection.

Photography is a medium entirely dependent on the passage of time. The supposed reality the photograph presents is most frequently only a simple fraction of a section, maybe even a thousandth of a second. Yet the resulting image has an after-life that is as long as the history of photography itself. Certain methods of colour printing can now provide a shelf-life for the photograph that is as yet immeasurable. The colours are, more or less – given a century or so, permanent. In the mental archive we know as our memory the photographs are often un-eradicable. They are lodged there for as long as we have consciousness with which to access them from the archive. Yet they are born in a split-second. This division of time supposes that time must be continuous, rather than a cycle of emergence and decay, as we observe in the natural world. If there were a gap between the emergence or the birth of a fraction of time and its decay or passing, that gap would be the window to another parallel world. That possible gap interests Tim. Lili can take on a parallel existence, whether it be suggested in stone or on film or video. She can come to life as if slipping through a gap and then falling headlong like ‘Alice in Wonderland’, or perhaps more pertinently like ‘Alice Through the Looking Glass’, into the other world, the secret but ever-present alternative realm. The idea of co-existing realities is fundamental to Tim’s way of seeing.

It is well known in the West that ‘Alice in Wonderland’ (1865) and Alice Through the Looking Glass’ (1871), two fantastic novels by Lewis Caroll, which were immensely popular in Victorian England, were written under a pseudonym. Their author, the Reverend Charles Dodgson, was a mathematician at Oxford. Alice was based on a ten-year-old girl called Alice Liddell, the daughter of the Vice-Chancellor of the university. Beneath the intricacies of the tales was a symbolism that made great play with the limits of mathematical knowledge of the time. Alice, by falling through a great rabbit hole or passing through a mirror, entered parallel worlds. Concepts of numbers and mathematical logic were embedded in the stories. Curiously, Lewis Carroll is also known as a leading amateur photographer of the period and was an expert in the wet collodion process. Alice, beside a number of other young girls, became one of his favourite subjects. His mathematical investigations seemed to balance what might have verged on an erotic obsession with pre-pubertal girls, and there is evidence of torment. The Victorian era is known as one of suppression, which was only broken when Sigmund Freud opened the floodgates to the subconscious with the publication of ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ in November 1899, literally on the cusp of a new century. The Reverend Dodgson may have personified some of the conflicts of his time with a restless sense of inquiry and a desire much laden with guilt. Alice was a medium. He could channel his exploration through her. She began as the attentive listener to one of his stories and then became their subject. She was not inanimate, but she was the embodiment of innocence, as yet uncorrupted by the foibles of adulthood.

In the wake of Freud came surrealism and with it the overt sexualisation of the shapes of the exterior world as the sexual anatomy that had lurked in the subconscious then rose to the surface and was made explicit. Man Ray was to make a pornographic display of copulating wooden figures. Hans Belmer was to draw endless pictures of sexual penetration exquisitely. Using photography he recorded his array of dolls, which sprouted limbs in re-arranged positions around enlarged vaginal folds. The sexualisation of the doll lingered, as did the Alice and Lolita, in common erotic language. In Japan it still exists with its own literature and publications. The doll remains sexualised as long as you can project on to ‘her’ whatever you wish, and the more so in an otherwise repressed environment.

The manikin Lili does appear naked finally. She does not offer us, male viewers, any erotic thrill. The photographs of her nude are more about Lili acquiring her own sexuality, or appearing to do so. But as we see her stripped of her clothes, she is also stripped of her illusion. She is no more than a set of mechanically articulated limbs.

With Lili’s physical presence laid bare we are left with no more than a memory. In fact, Lili never was more than a memory. She presented a platform on which a fragment of memory could be preserved. In of herself, she is meaningless – a vacuum. She allows us to recall. We may find some element of erotic history in her gaze, just as we may find some sense of loss or of the passage time as we catch a glance of her. We impose our own story on her. We live at a time when memory is a defining factor. We know that our genetic memory that carries the history of evolution is stored in the information deep in the nucleus of the single cell. We know that as cities are torn down and rebuilt so our collective memories change. We inhabit places where the old and the new worlds collide. In these places memories are preserved like ancient monuments against the encroaching shift of cultural change. Memory becomes all the more important when the virtual supplants the physical, as it does in so many areas of our lives. We become adults forgetful of childhood and its secret places. The nourishment of memory, which Lili can provide, is the first line of the defence of our imagination.

Silent Passenger goes one step further: by photographing a mannequin as if it were a real person, Yip questions whether it is a deception when we choose to accept something to be true, even when we know it is not.